In this blog post post I describe:

- how to use standard Ctrl keyboard shortcuts when using Dyalog on all platforms.

- little-known APL input features for Microsoft Windows.

- alternative input methods that do not use the Ctrl key for APL input.

I don’t personally use the official Dyalog IME for Microsoft Windows as my daily APL input method. My only complaints are that it forces me to use the Ctrl key for APL input, which conflicts with conventional shortcuts for most applications, and for some reason it puts an additional item in my input method list because I have a Japanese input enabled, even though that is not a supported layout for the IME!

I am a fan of Adám’s AltGr keyboard for Windows for a couple of reasons. It is based on the Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator (MSKLC), and appears to work in newer Universal Windows Platform (UWP) apps and with the default On-Screen Keyboard on Windows. It also has accents and box-drawing characters. However, support might be unreliable, because Microsoft do not officially support MSKLC on Windows 11, and there are rumoured issues with using it on ARM machines. Its main drawback is the limited choice of shifting keys, which can make it difficult to use with certain keyboard layouts or in certain applications. Personally, I am fond of using Caps Lock as my primary APL shifting key, because it is rare these days that I need to TYPE A BUNCH OF THINGS IN ALL CAPITALS – it feels like shouting.

I used to do this by mapping Caps Lock to Alt Gr through some registry trickery. However, Kanata allows me to use almost any keys I like. I now have Caps Lock and Right Ctrl as APL shifting keys. In addition, I can double-tap Caps Lock to toggle it, so I can SHOUT OVER TEXT if I really need to. It’s cross-platform, so my single APL Kanata configuration gives me a consistent experience even when using my Linux virtual machine. There are still many features on my wish list for a comprehensive input method editor, but this is quite good for now (I wonder if anybody is able to adapt mozc for APL?).

Whichever keyboard input method you use, once you are not using Ctrl for APL input you will be very glad to get back your beloved, conventional keyboard shortcuts for use in the Dyalog editor.

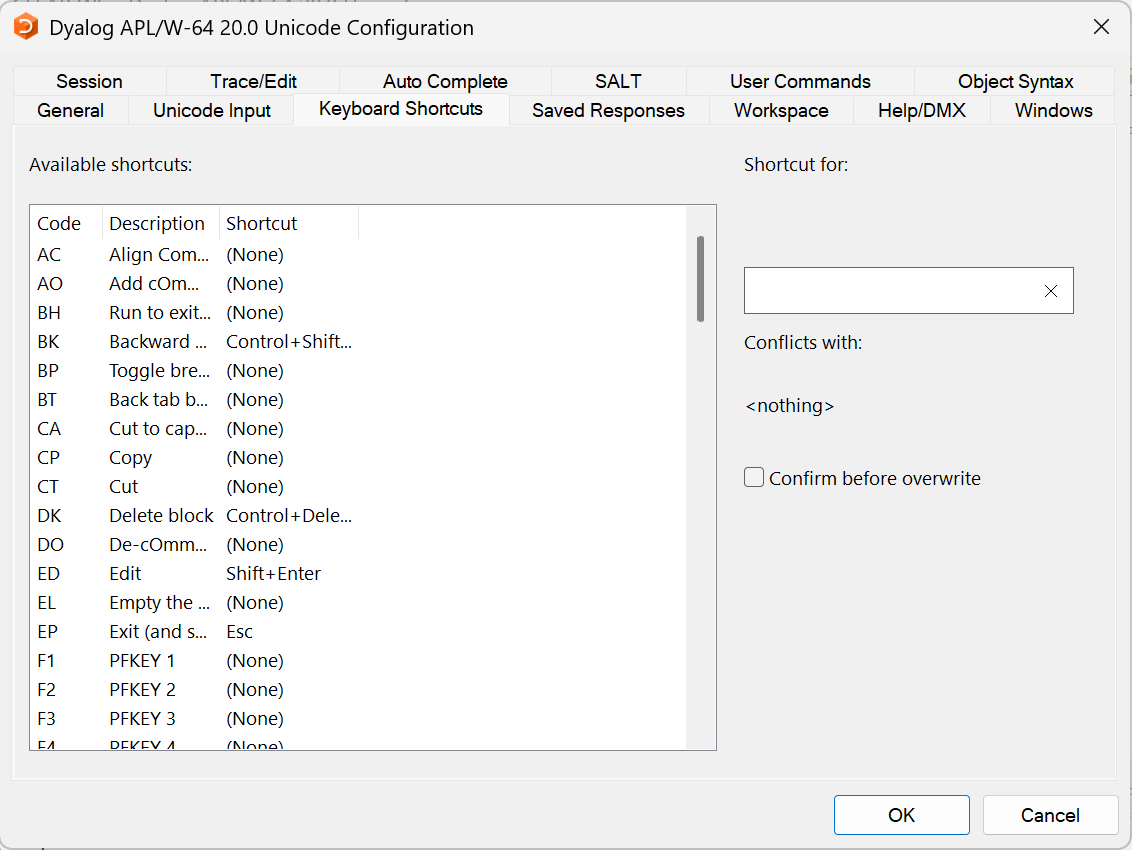

In the Dyalog IDE for Microsoft Windows, you can set keyboard shortcuts by selecting Options > Configure in the Session’s menu bar, then selecting the Keyboard Shortcuts tab. From here, you can click on a code that corresponds to an action for which you want to set a shortcut.

These are keyboard shortcuts recognised by the Dyalog development environment.

I set:

- <FX> to Ctrl+S to save changes in the editor without closing it

- <SA> to Ctrl+A to select all text in a window

- <CP> to Ctrl+C to copy text

- <CT> to Ctrl+X to cut text

- <PT> to Ctrl+V to paste text

- <SC> to Ctrl+F to search and find text in the session log, editor, and debugger

- <RP> to Ctrl+H to search and replace text in the session log, editor, and debugger

To help find these in the list, click on the Code column title to put them in alphabetical order.

In Ride, only <FX> needs to be set, as the other shortcuts should default to this behaviour.

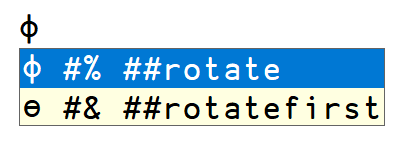

Having said all that, the official Dyalog IME still has features that would be invaluable especially if I were a brand new user. You can read about these in the Dyalog for Microsoft Windows UI guide and configure them using the IDE by going to Options > Configure > Unicode Input > Configure Layout. A little-known tip is that its backtick (also known as introducer or prefix) input method offers a searchable keyword menu, so that you can find glyphs by name or by the name of the function or operator it represents.

After setting the prefix introducer key to # (octothorpe / hash), pressing twice and typing “rot” shows suggestions for the glyphs ⌽ and ⊖ with the keywords “rotate” and “rotatefirst”.

There’s also the wonderful overstrike feature. Once upon a time, APL was executed on remote machines accessed using the IBM Selectric Teletype typewriter; you can see this in this demonstration from 1975. Certain characters would be composed by typing one symbol over another, such as printing a vertical bar (|) over a circle (○) to produce the circle-bar glyph for rotate/reverse (⌽).

Its basic usage is a feature of the IDE for Microsoft Windows; the IME isn’t required at all. If you press the Ins key on your keyboard, it usually toggles “insert” or “overtype” mode. This is typically indicated by the vertical bar text cursor changing into an underbar. Typing will then replace existing text indicated by the cursor. With overstrikes enabled, APL glyphs can be created using other glyphs!

Insert, Slash (/), LeftArrow, Dash (-), Circle (○), LeftArrow, Stile (|)

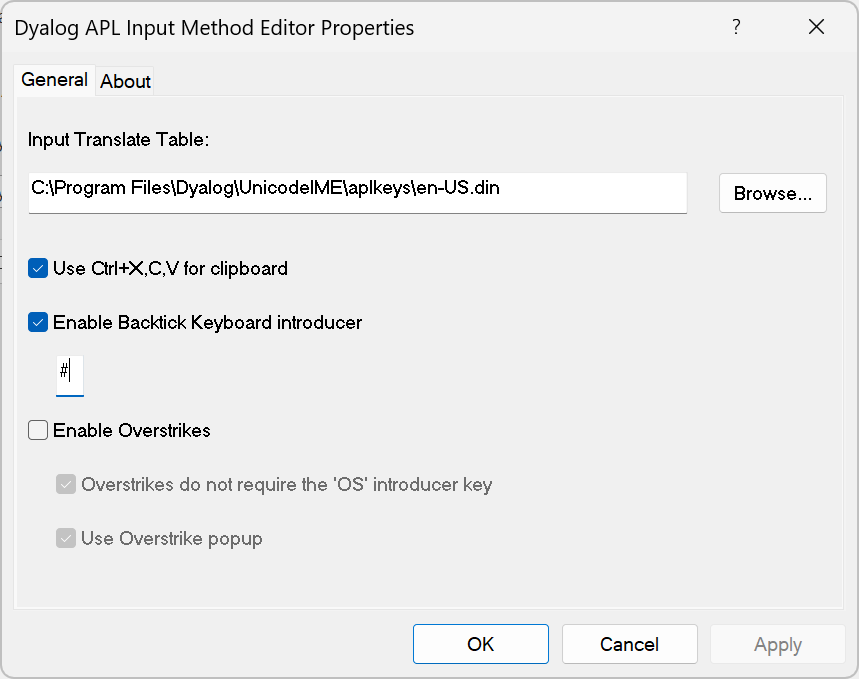

The IME allows you to use this in applications other than Dyalog by ticking Enable Overstrikes from the IME settings. You can read the documentation to learn more, but the basic mechanism is to use the Overstrike Introducer Key (default Ctrl+Backspace) followed by entering the two symbols to overstrike.

Settings menu for the Dyalog Input Method Editor

For this post I just wanted to highlight aspects of APL input beyond the simple defaults. For more about using your keyboard with Dyalog, see Adám’s blog post about enhanced debugging keys.

Follow

Follow