Let me take you back to the 1970s. We’re playing Space Invaders in the arcade, watching Star Wars in the cinema, and listening to David Bowie in our Minis. When we come home and open our terminals to use APL, all of our arrays are flat. Nested arrays will not be part of a commercial APL implementation until NARS is released in 1981. Performing computations on, say, a list of names, is not as straightforward as we might hope!

We might choose to keep each name in a row of a matrix. For example:

M←4 7⍴'Alice Bob CharlieBen '

M

Alice

Bob

Charlie

BenAlternatively, we might choose to delimit each name with a ';' (or another suitable delimiter). For example:

V←';Alice;Bob;Charlie;Ben'If we want to count the number of names beginning with a 'B', we can’t simply call +/'B'=⊃¨names, but have to think about our representation:

+/'B'=M[;⎕IO]

2

+/'B'=(¯1⌽V=';')/V

2We don’t know it yet, but 50 years later, these types of expressions will have excellent performance on the computers of the day. They will also be the key to outperforming the nested arrays that will be introduced in the 1980s.

⍝ let's use bigger data

M←10000000 7⍴M

V←(2500000×⍴V)⍴V

N←10000000⍴'Alice' 'Bob' 'Charlie' 'Ben'

⍝ see how much faster the non-nested versions are!

]Runtime -c "+/'B'=M[;⎕IO]" "+/'B'=(¯1⌽V=';')/V" "+/'B'=⊃¨N"

+/'B'=M[;⎕IO] → 4.1E¯3 | 0% ⎕

+/'B'=(¯1⌽V=';')/V → 1.2E¯2 | +192% ⎕⎕

+/'B'=⊃¨N → 2.8E¯1 | +6863% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕The above example is an illustrative benchmark, but it shows what’s possible.

In this blog post, I’m going to explore various techniques to leverage flat representations of nested data. I’ll look at querying and manipulating these representations, and see how the concrete array representation that Dyalog APL uses affects performance.

How Arrays are Stored

The Dyalog interpreter stores your flat arrays in memory as a header (which includes some bookkeeping information needed by the interpreter) followed by the shape of the array, and then the contents of the array in ravel order. For example, 2 3⍴⎕A looks like this:

┌─────┬─────┬─────────────┐

│ ... │ 2 3 │ A B C D E F │

└─────┴─────┴─────────────┘Nested arrays are more complicated. Every element is stored separately, potentially at a distant location in memory. A nested array is still stored with a header and shape, but the body consists of addresses of the array’s elements, rather than the elements themselves. These addresses tell the interpreter where in the workspace to find each element of the nested array. This means that the array 'ABC' 'DEF' looks like this:

┌──────────┐

│ ↓

┌─────┬───┬─│───┐ ┌─────┬───┬───────┐ ┌─────┬───┬───────┐

│ ... │ 2 │ * * │ ... │ ... │ 3 │ A B C │ ... │ ... │ 3 │ D E F │

└─────┴───┴───│─┘ └─────┴───┴───────┘ └─────┴───┴───────┘

│ ↑

└────────────────────────────────┘Sometimes, the interpreter can detect that you’re reusing an array for multiple elements, and refer to it multiple times, rather than copying. For example, 4⍴⊂'ABC' is stored as:

┌─┬─┬─┬────────┐

│ │ │ │ ↓

┌─────┬───┬─│─│─│─│─┐ ┌─────┬───┬───────┐

│ ... │ 4 │ * * * * │ ... │ ... │ 3 │ A B C │

└─────┴───┴─────────┘ └─────┴───┴───────┘This layout has a few consequences for us:

- Nested arrays need to store extra information for each of their elements – the header and the shape. Although this is patially mitigated by the trick above, this space requirement quickly grows if you have many nested elements!

- Accessing the elements of nested arrays can be slow. Modern hardware is optimised under the assumption that you won’t start doing work far away from where you are already working. However, when you access an element of a nested array, that element could be stored very far away in the workspace, so your computer could take a while to load it.

When looking at the performance of algorithms involving arrays, doing as much as possible to reduce nesting will often yield good results.

Partitioned Vectors

Although I looked at using matrices in the previous section, I’m going to focus on using partitioned vectors from now on. Using matrices mostly involves multiple references to the rank operator (⍤), while using a partitioned vector is much more interesting.

There are many ways to represent the partitioning of a vector into multiple sub-vectors. I’ve already shown one way – delimiting the sub-vectors with a character that does not itself appear in any sub-vector:

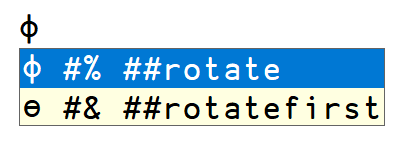

V←';Alice;Bob;Charlie;Ben'Here, a delimiter precedes the content of each sub-vector. This is very useful; if I need to know the delimiter, I can find it with ⊃V. I could also place the delimiter after each sub-vector, making it easy to convert between these representations with a rotate:

1⌽V

Alice;Bob;Charlie;Ben;This is the format you get from reading a file with ⎕NGET 'filename' 1, with linefeed characters (⎕UCS 10) replacing semicolons as the trailing delimiters.

You can also store the partitions in a separate array from the sub-vectors. For example, you could use a Boolean mask to indicate the start of each sub-vector:

data←'AliceBobCharlieBen'

parts←1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0

[data ⋄ parts]

A l i c e B o b C h a r l i e B e n

1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0Note: this example uses array notation, a new feature available in Dyalog v20.0. Using array notation, [a ⋄ b ⋄ c] defines an array with a, b, and c as major cells. This is convenient when viewing vectors whose contents align.

One benefit of this format is that you can include any character in a sub-vector without worrying about cutting it in half by including a delimiter. I will return to this way of representing partitions later, but it’s not the only option. For an in-depth exploration, see this essay on the APL Wiki.

Partitioned Searching

Before I continue, I want to examine some timings, so I need some large, random data to work with. I’m going to use the list of English words used for spell-checking on my machine. I’ll use ⎕C to case-fold each word so that I can ignore case. This list is ordered alphabetically, but I’m not going to take advantage of that here.

N←⎕C¨⊃⎕NGET'words.txt'1 ⍝ load the words as a nested vector

⍴N ⍝ how many are there

479823

V←∊';',¨N ⍝ delimited vector to work with

100↑V ⍝ what does it look like

;1080;10-point;10th;11-point;12-point;16-point;18-point;1st;2;20-point;2,4,5You can also use ⎕NGET to load the words into a flat array directly, which is significantly faster.

]Runtime -c "∊';',¨⊃⎕NGET'words.txt'1" "';'@{⍵=⎕UCS 10}¯1⌽⊃⎕NGET'words.txt'"

∊';',¨⊃⎕NGET'words.txt'1 → 5.3E¯2 | 0% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕

';'@{⍵=⎕UCS 10}¯1⌽⊃⎕NGET'words.txt' → 2.8E¯2 | -48% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕ Text is not the only type of data that you might want to store efficiently; for example, you might need to store DNA strings or numeric vectors. However, I’m going to use text in this example.

I’ve already demonstrated a very basic example of searching a partitioned vector for a pattern – I counted the number of names beginning with 'B'. Let’s investigate how that really worked. I’ll start by finding a mask of the delimiter preceding each word:

m←V=';'

20(↑⍤1)[V ⋄ m]

; 1 0 8 0 ; 1 0 - p o i n t ; 1 0 t h ;

1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1If I rotate this mask to the right by one place, it now corresponds to the first letter of each word:

20(↑⍤1)[V ⋄ ¯1⌽m]

; 1 0 8 0 ; 1 0 - p o i n t ; 1 0 t h ;

0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0I can use this rotated mask to pick out the first character of each word; it then becomes easy to count the words beginning with 'b' (not 'B' anymore, as I case-folded the words):

50↑(¯1⌽m)/V ⍝ first character of each of the first 50 words

111111112222223333334444455566778899-aaaaaaaaaaaaa

+/'b'=(¯1⌽m)/V ⍝ number of words that start with a 'b'

25192

+/'b'=⊃¨N ⍝ double check answer against nested

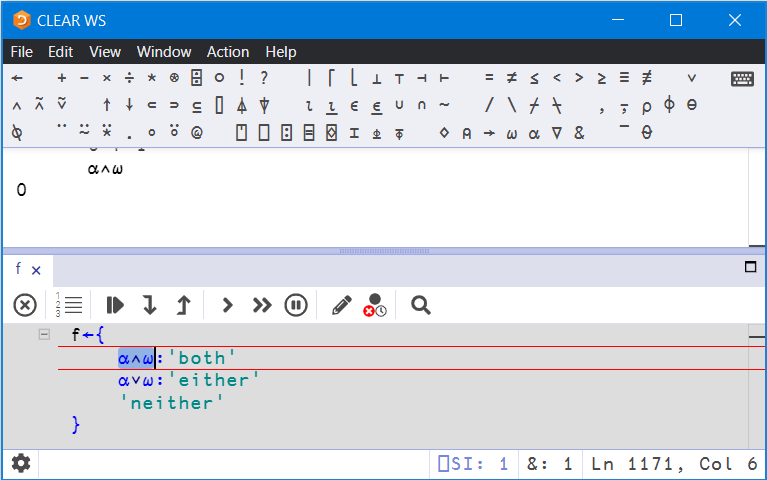

25192Now for something more complicated. Say I want to count the number of words beginning with the prefix 'con'. I could reuse the previous technique to find the first character of each word, and tweak it to find the second and third characters as well:

⍝ ┌─ starts c ─┐ ┌── then o ──┐ ┌── then n ──┐

+/('c'=(¯1⌽m)/V)∧('o'=(¯2⌽m)/V)∧('n'=(¯3⌽m)/V)

3440I need to be careful here! Some words in the list are shorter than 3 letters, so when I rotate the mask, I start picking from the following word. Fortunately, I’ve included the delimiters, so when I cross a word-boundary, one of the tests will evaluate to false. If I stored a partition representation separately to the data, I would need to handle this case.

There’s a nice way to use find (⍷) to solve this problem. As the start of a word is explicitly encoded by a ';' in our data, I can search directly for the start of a word followed by 'con'.

+/';con'⍷V

3440Both of these methods are much faster than acting on the nested data:

]Runtime -c "+/{'con'≡3↑⍵}¨N" "+/('c'=(¯1⌽m)/V)∧('o'=(¯2⌽m)/V)∧('n'=(¯3⌽m)/V)⊣m←V=';'" "+/';con'⍷V"

+/{'con'≡3↑⍵}¨N → 4.3E¯2 | 0% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕

+/('c'=(¯1⌽m)/V)∧('o'=(¯2⌽m)/V)∧('n'=(¯3⌽m)/V)⊣m←V=';' → 2.5E¯3 | -95% ⎕⎕

+/';con'⍷V → 3.3E¯3 | -93% ⎕⎕⎕Great, I can count things at the start of words… but things get really interesting when I want to count things occurring anywhere in a word, as I need to get creative with using delimiters as anchors.

Say I want to count the number of words which contain the letter 'a'. I can get a mask of all the occurrences of it, but as a word can contain more than one 'a', I have to be clever about counting. I’ll select some test data to see what’s going on:

test←';abc;xyz;banana'There are several ways to count the words here that countain an 'a'. The first is to use a scan of the occurrences of a delimiter to give a unique identifier for each word. I can then use the occurrences of 'a' to select these IDs. The number of words that contain an 'a' is then the number of unique IDs:

[

test ⍝ data

test=';' ⍝ mask of delimiters

+\test=';' ⍝ word IDs

test='a' ⍝ mask of 'a's

]

; a b c ; x y z ; b a n a n a

1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1

(test='a')/+\test=';' ⍝ word IDs of each 'a' (one in 'abc', three in 'banana')

1 3 3 3

≢∪(test='a')/+\test=';' ⍝ number of unique IDs

2Note: this example again uses array notation, a new feature available in Dyalog v20.0. Line breaks can be used in place of ⋄s in array notation; I have used this option here to evaluate each row of a matrix on its own line.

I want to check that this also works on large input:

⍝ try it on the large input

≢∪(V='a')/+\V=';'

281193

⍝ double-check against the nested format

+/∨/¨N='a'

281193

⍝ and it's faster

]Runtime -c "+/∨/¨N='a'" "≢∪(V='a')/+\V=';'"

+/∨/¨N='a' → 5.2E¯2 | 0% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕

≢∪(V='a')/+\V=';' → 4.6E¯3 | -91% ⎕⎕⎕⎕That’s one way to solve this problem, but there are many more and I’m sure the interested reader will come up with their own. Here are a few alternatives for inspiration:

≢∪(V=';')⍸⍥⍸V='a'

281193 +/';a'⍷V∩'a;'

281193 +/1≠¯2-/(⍸,⎕IO+≢)';'=V∩'a;'

281193 +/2</0,(1⌽V=';')/+\V='a'

281193 (V=';'){+/(⍺/⍵)≥a/1⌽a←⍺/⍨⍵∨⍺}V='a'

281193I’m going to have a closer look at how the last two of these work in part 2 of this post. For now, I’ll move beyond counting and do some structural manipulation with this format.

Partitioned Manipulation

Filtering

Some manipulations on the delimited format are as easy as they would be with the nested format. Say you’re interested in the distribution of vowels among words (a, e, i, o, and u in English). You might then want to pare down your list of words to include only the vowels. With our delimited format, this is simple:

test←';the;quick;brown;fox;jumps;over;the;lazy;dog'

(test∊';aeiou')/test ⍝ one way

;e;ui;o;o;u;oe;e;a;o

test∩';aeiou' ⍝ another way

;e;ui;o;o;u;oe;e;a;oBesides remembering to preserve the delimiter, there’s nothing tricky going on here. Don’t get too comfortable though, things are about to get trickier!

So that I can continue to check my answers against the nested representation, I will define a utility function to split a delimited vector into a nested representation:

Split←{1↓¨(⍵=';')⊂⍵}

Split test

┌───┬─────┬─────┬───┬─────┬────┬───┬────┬───┐

│the│quick│brown│fox│jumps│over│the│lazy│dog│

└───┴─────┴─────┴───┴─────┴────┴───┴────┴───┘I can now test filtering against the nested representation:

(Split V∩';aeiou')≡(N∩¨⊂'aeiou')

1You can also write Split as {(⍵≠';')⊆⍵}, but this fails on some edge cases. Can you see which ones?

As well as filtering the letters of a word, I might want to filter words out of the whole list. I could do this filter on any condition; for now, I’ll use a condition that I know how to compute already and filter for words that begin with 'con'. Once I have identified the places in the delimited vector that indicate words beginning with 'con', I can find the word ID for each of those places, and use those IDs to construct a mask to filter the data:

test←';banana;cons;conman;apple;convey'

ids←+\test=';' ⍝ word IDs

(';con'⍷test)/ids ⍝ IDs of words that start with 'con'

2 3 5

m←ids∊(';con'⍷test)/ids ⍝ mask of words that start with 'con'

[test ⋄ ';con'⍷test ⋄ ids ⋄ m] ⍝ see how those line up

; b a n a n a ; c o n s ; c o n m a n ; a p p l e ; c o n v e y

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 5

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

m/test ⍝ only words that start with 'con'

;cons;conman;conveyI’ll try it on the big data and compare the result to the nested version:

answer←V/⍨ids∊(';con'⍷V)/ids←+\V=';'

(Split answer)≡{'con'≡3↑⍵}¨⍛/N

1Note: this example uses the behind operator (⍛), a new feature available in Dyalog v20.0.

This method seems to work perfectly, but what is the performance like?

]Runtime -c "{'con'≡3↑⍵}¨⍛/N" "V/⍨ids∊(';con'⍷V)/ids←+\V=';'"

{'con'≡3↑⍵}¨⍛/N → 3.8E¯2 | 0% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕

* V/⍨ids∊(';con'⍷V)/ids←+\V=';' → 1.1E¯2 | -73% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕Note the * by the delimited version. This indicates that the result is different to the result of the nested version. However, this is to be expected; I did not include the Split in the timings, so the result formats are different. However, I know that the results match if I ignore the format, as I checked them before.

Reversing

Continuing the tour of miscellaneous things that you might like to do with a delimited vector, let’s look at reversal. With filtering, filtering the contents of each word turned out to be less complicated than filtering whole words. With reversal, the reverse (haha!) is true. The technique to reverse each word builds on the technique to reverse the order of the words.

The key will be the vector of word IDs that I’ve used before. To reverse the order of the words, I can use the grade of the word IDs directly to sort our data. This works because word IDs are increasing along the vector, so by grading the IDs down, I fetch larger IDs (later words) to the start of the result. It also relies on ⍒ being stable, meaning that the order of elements with the same value (that is, letters within a word) is preserved.

test←';first;second;third'

ids←+\test=';'

test[⍒ids]

;third;second;first

⍝ how everything lines up

[test ⋄ ids ⋄ ⍒ids ⋄ test[⍒ids]]

; f i r s t ; s e c o n d ; t h i r d

1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3

14 15 16 17 18 19 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 1 2 3 4 5 6

; t h i r d ; s e c o n d ; f i r s tI can build on this to reverse the letters of each word. Notice that if I reverse this result, I get almost exactly what I need; each word is back in its original position, with its letters in the reverse order:

⌽test[⍒ids]

tsrif;dnoces;driht;The only issue is that the delimiters are now trailing, rather than leading, but that’s easily fixed with a rotate:

¯1⌽⌽test[⍒ids]

;tsrif;dnoces;drihtAs a matter of taste, I prefer to do all the manipulation on the grade vector rather than on the result:

test[¯1⌽⌽⍒ids]

;tsrif;dnoces;drihtIsn’t that nice? When I first thought about doing real manipulations on this format, I didn’t expect the code to be so simple. For completeness, here are the usual checks and timings:

⍝ check the results are correct

(⌽N)≡Split V[⍒+\V=';']

1

(⌽¨N)≡Split V[¯1⌽⌽⍒+\V=';']

1

⍝ look at the runtimes

]Runtime -c "⌽N" "V[⍒+\V=';']"

⌽N → 2.9E¯3 | 0% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕

* V[⍒+\V=';'] → 1.5E¯2 | +419% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕

]Runtime -c "⌽¨N" "V[¯1⌽⌽⍒+\V=';']"

⌽¨N → 1.7E¯2 | 0% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕

* V[¯1⌽⌽⍒+\V=';'] → 1.8E¯2 | 0% ⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕⎕ What’s happening here? Our fancy flat techniques are supposed to give us superior performance! Well, recall how arrays are stored. To reverse a nested array, all the interpreter has to do is reverse the addresses of the nested elements – it doesn’t have to touch the contents of those elements at all:

┌─────┬───┬───────┐ ┌─────┬───┬───────┐

│ ... │ 3 │ * * * │ →becomes→ │ ... │ 3 │ * * * │

└─────┴───┴─│─│─│─┘ └─────┴───┴─│─│─│─┘

┌─┘ │ └─┐ └─│─│─┐

│ │ │ ┌───│─┘ │

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

┌─┐ ┌─┐ ┌─┐ ┌─┐ ┌─┐ ┌─┐

│A│ │B│ │C│ │A│ │B│ │C│

└─┘ └─┘ └─┘ └─┘ └─┘ └─┘By contrast, our flat version needs to process every letter of every word. It also needs to perform a grade, which is relatively expensive.

The difference evens out when I record the time taken to reverse each word. This is likely because the nested version now has to traverse every nested element doing a reversal, while the flat version only needs to do the relatively cheap extra work of ¯1⌽⌽.

To Be Continued…

In conclusion, this flat format is not a magic bullet for performance, it really depends on exactly what you want to do with it. If you’re doing a lot of searching, then using a flat format might be what you need, but if you’re doing more manipulatating, then a nested format might be better. The only way to know is to write the code and test the performance on representative data!

I’ve covered some interesting ways to process character data in this flat format, but it doesn’t stop there! I haven’t yet touched on numeric or Boolean data at all, and that’s where things get really interesting. If we have a partitioned vector, how might we sum each sub-vector? How might we do a plus-scan on each sub-vector? Will this be faster or slower than nested equivalents? The second part of this post (coming soon!), will give the answers to these questions and more.

Follow

Follow